Stakeholder engagement and social media are like distant relatives, deeply connected but rarely together. They offer a powerful and authentic direction to an organisation, when brought together. In our experience, large organisations often split responsibility for social media monitoring and engagement between different teams: brand and customers services being historically separate from corporate relations and stakeholder engagement. Many smaller organisations are focussing their social media on brand building with a few realising the power of this tool to engage stakeholders. Integrated social engagement is key.

Here are three ways social media and stakeholder engagement are better together…

1. Joined up stakeholder communication

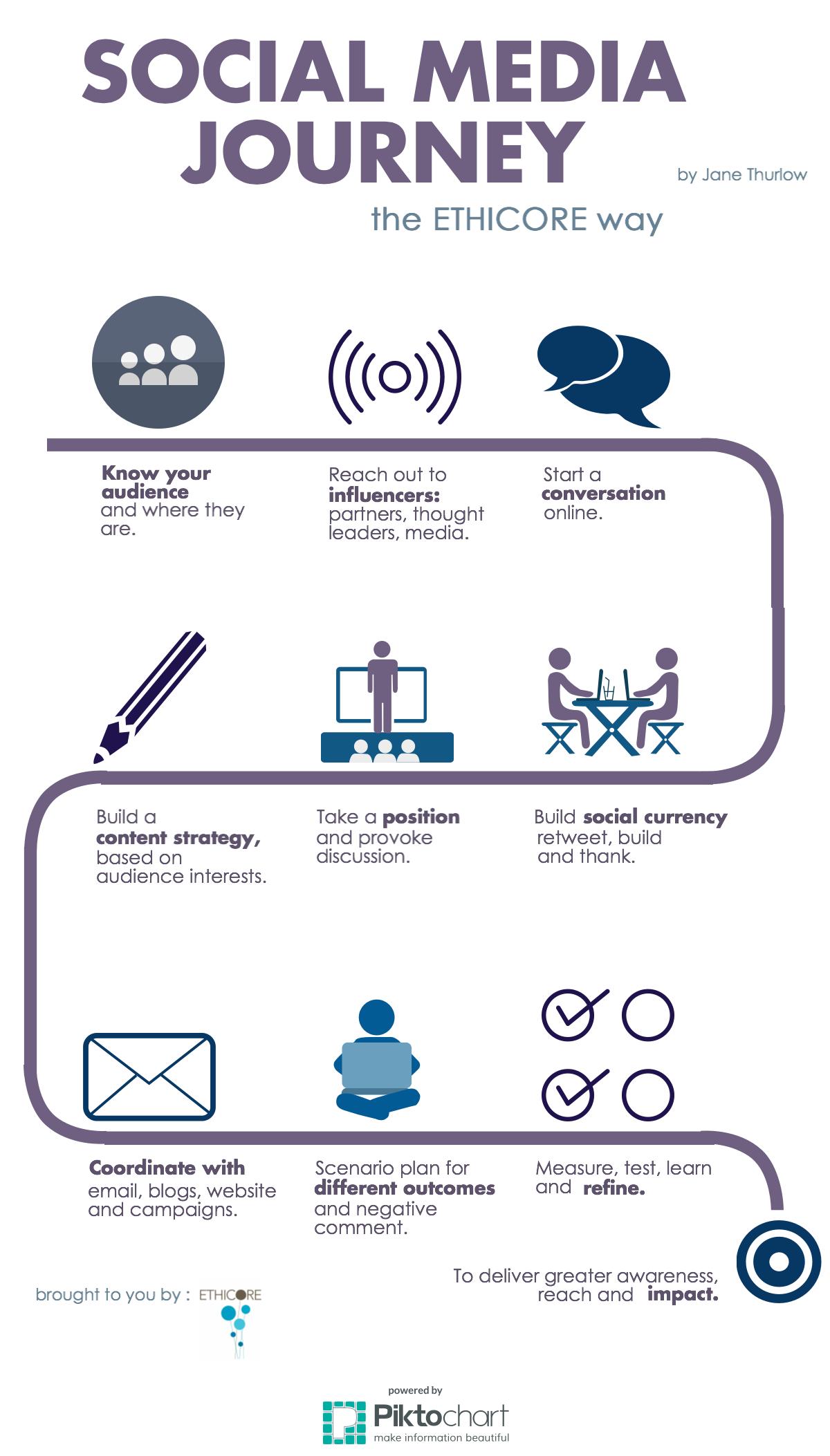

Social media channels give organisations the ability to listen to, engage with and respond to their stakeholders in an open and flexible way: the building blocks of a trusting relationship. You might think that this is an organic process? As with any communication strategy, management of social media needs objectives, audience segmentation and insights and a plan for different channels. LinkedIn is great for corporate and financial stakeholders, Facebook for customers and service users, with Twitter tailored for both audiences. Stakeholder engagement via social media requires detailed planning and a personal approach, no matter what part of the organisation delivers it.

2. Reputational management and brand health

Social media enables us to listen to stakeholders and ‘mine for sentiment’, to see how they feel about our brands. Some of our most active and potentially critical stakeholders will be active on social media. Clearly engaging in a meaningful way with these individuals – customers, activist groups, employees – is critical to brand perception AND corporate reputation. Never has reputation and brand management been so closely meshed and we have the tools at our fingertips to manage these two areas in a meaningful and accessible way. We just need to create the internal structures to facilitate this.

3. Consistent use of content – say it loud

Content is king and social media provides some of the most engaging routes to share. Creative content generation isn’t just for consumers but for all your stakeholders: customers, shareholders, employees, community groups and activists. This is where consumer and brand digital strategists are ahead of the game. What’s needed is skill sharing and an integrated approach to content generation, giving stakeholders great quality content, reformatting it for different audiences. Result? Greater engagement and dialogue.

A truly integrated approach to social engagement can be developed through organisational design and/or detailed ‘engagement’ planning. Either way, social media and stakeholder engagement are better together, facilitating deeper engagement and more effective use of existing skills and knowledge.

Jane Thurlow and Rachael Clay